Lab 4: Solutions¶

In this lab, we will begin to build various tools to fit a model to data. The goal is to understand, implement and compare chi2 and MCMC fitting routines to fake data. In Lab 5, we will apply these tools to real spectroscopic data from Keck / DEIMOS.

The goals of the lab are:

Use python modules to perform \(\chi^2\) fits on data

Write and compare to your own \(\chi^2\) algorithm

Explore sampling algorithms

Write an MCMC algorithmm and compare to \(\chi^2\) results

Question 1¶

Do Exercise 1 from Hogg, Bovy & Lang (2010) using a standard python routine of your choice. The data (Table 1) are available in the A330 public page under Data Access as well as in your Git directories (as the file is small). Please report your best fit values and errors on these values. These should be very close to those in Figure 1 of the paper.

Tip

If you are using np.polyfit, set the cov='unscaled keyword in polyfit to have it return not only the fit coefficients, but also the full covariance matrix. The parameter uncertainties, assuming no off-axis covariance, are the square roots of the diagonal terms (of which for a linear fit there will be 2. You can pull the diagonal terms of a square array using np.diag().

from astropy.io import fits, ascii

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# LOAD DATA FROM HOGG et al 2010, Table 1

data = ascii.read('hogg_2010_data.txt')

# SKIP THE FIRST FEW DATA POINTS

m=data['ID'] > 4

data=data[m]

To fit the data, I’ll use numpy’s polyfit below. We determine the errors from the diagonals of the output covarience matrix.

An alternative option is scipy.optimize.curve_fit.

p,pcov = np.polyfit(data['x'],data['y'],1,w=1./data['sigma_y'],cov='unscaled')

perr = np.sqrt(np.diag(pcov))

print('Best fit slope: {:0.2f} +/- {:0.2f} '.format(p[0],perr[0]))

print('Best fit intercept: {:0.1f} +/- {:0.1f} '.format(p[1],perr[1]))

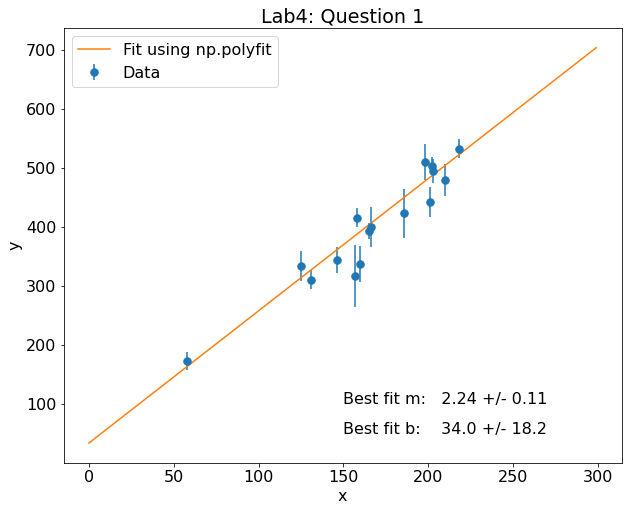

Best fit slope: 2.24 +/- 0.11

Best fit intercept: 34.0 +/- 18.2

Cool, this is very close to the results shown in Figure 1 of Hogg et al (2010). Now, let’s plot the results. I will use the coefficients of the fit to create an object called pfit from which I can generate the best-fitting line.

fig,ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10,8))

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 16})

plt.errorbar(data['x'],data['y'],yerr = data['sigma_y'],fmt='.',label='Data',ms=15)

pfit = np.poly1d(p)

x=np.arange(0,300)

plt.plot(x,pfit(x),label='Fit using np.polyfit')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.legend()

plt.title('Lab4: Question 1')

plt.text(150,100,'Best fit m: {:0.2f} +/- {:0.2f} '.format(p[0],perr[0]))

plt.text(150,50,'Best fit b: {:0.1f} +/- {:0.1f} '.format(p[1],perr[1]))

Text(150, 50, 'Best fit b: 34.0 +/- 18.2 ')

Note

Another way to turn np.polyfit fit (coefficient arrays) into actual curves is via np.polyval, which takes in the p above along with the array of values where you want to evaluate the polynomial.

Question 2¶

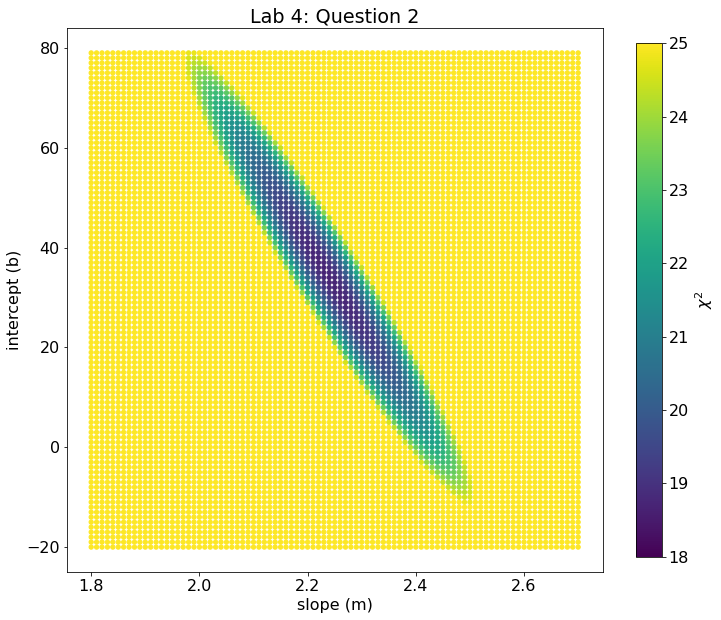

Repeat the question above, however, this time write your own script to solve this problem by evaluating chi2 on a grid of m and b values. You should write a chi2() function that reads in 4 arguments m,b,data_x,data_y,unc_y (though you can call them what you want). You should then write a fit_line() or minimize_chi2() function that will, across your grid of \(m\) and \(b\) values, evaluate chi2 using your chi2() function. You may use the values above to guide your grid, making sure the grid spans at least 2-sigma in both directions.

Plot the chi2 values for all grid points. We suggest creating an array, chi2_image, which is a shape characterized by the lengthd of your m_grid and b_grids. Then, as you double-for-loop over m and b values and calculate chi2, you can set chi2_image[i,j] to the output chi2 value.

Tip

Remember, \(m\) and \(b\) values won’t index your array directly. So you’ll want to loop via something like for i,m in enumerate(m_grid): and for j,b in enumerate(b_grid): if you’re going to do that.

While chi2 fitting is reliable for determining the best-fit values, it is not always easy to estimate errors on these parameters. For example, in the above example, we had to explicitly initialize a grid of parameters to fit on, and as soon as this grid has to get finely spaced, or moves into any number of dimensions > 2, everything gets much more computationally expensive to calculate, and understanding the chi-squared “surface” in multi-D becomes difficult. Additionally, we had to narrow in our range of \(m\) and \(b\) values to get it to work, but there may actually be a better solution elsewhere in parameter space that we’re not accessing.

def calc_chi2(m, b ,x ,y, yerr):

'''

Calculate chi2 value for a linear model.

Parameters

----------

m: float

slope of the line

b: float

y-intercept of the line

x, y: float

data points to be fit

yerr: float

one sigma errors on the y-values

Returns

-------

chi2

The value of chi2

'''

f = m*x + b

chi2 = np.sum((y - f)**2/yerr**2)

return chi2

Next we need to set-up a grid of parameters to search through. With two free parameters (m and b), this isn’t too difficult, but quickly gets complicated with more parameters.

m_grid = np.arange(1.8,2.7,0.01)

b_grid = 1.*np.arange(-20,80,1)

m_arr,b_arr,chi2 = [],[],[]

chi2_min = 1e8

m_min, b_min = 0,0

image = np.zeros(shape=(len(m_grid),len(b_grid)))

chi2 = []

for i,m in enumerate(m_grid):

for j,b in enumerate(b_grid):

c = calc_chi2(m,b,data['x'],data['y'],data['sigma_y'])

chi2.append(c)

m_arr.append(m)

b_arr.append(b)

image[i,j] = c

if c < chi2_min:

chi2_min = c

m_min = m

b_min = b

chi2 = np.array(chi2)

b_arr = np.array(b_arr)

m_arr = np.array(m_arr)

print('Best fit slope: {:0.2f} '.format(m_min))

print('Best fit intercept: {:0.1f} '.format(b_min))

print('Minimum chi2: {:0.1f} '.format(chi2_min))

Best fit slope: 2.24

Best fit intercept: 34.0

Minimum chi2: 18.7

Note

In the above, we store the output \(\chi^2\) values in two ways: in an array (chi2), and and in an “image” array in 2D at each m,b position. See how to plot the results from these two methods of storing the \(\chi^2\) values below.

# Scatterplot using the chi2 array

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12,10))

im = ax.scatter(m_arr,b_arr,c=chi2,marker='o',s=18,vmin=18,vmax = 25)

cb = plt.colorbar(im,ax=ax,shrink=0.945,label = '$\chi^2$')

ax.set_xlabel('slope (m)')

ax.set_ylabel('intercept (b)')

ax.set_title('Lab 4: Question 2')

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Lab 4: Question 2')

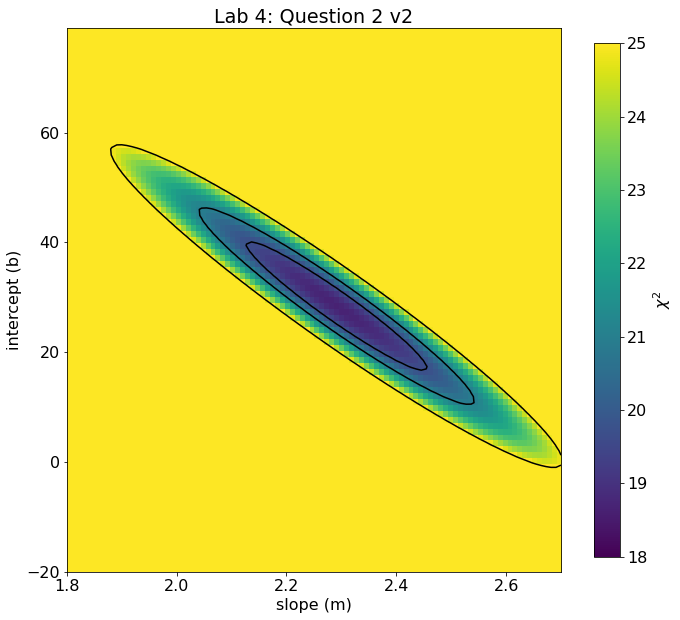

Alternatively, we can plot the \(\chi^2\) values a different way.

# using imshow on the 2D grid. This version makes contouring easier.

extent = [np.min(m_grid),np.max(m_grid),np.min(b_grid),np.max(b_grid)]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12,10))

im = ax.imshow(image,origin='lower',extent=extent,vmin=18,vmax=25,aspect=0.01)

cb = plt.colorbar(im,ax=ax,shrink=0.945,label = '$\chi^2$')

ax.set_xlabel('slope (m)')

ax.set_ylabel('intercept (b)')

ax.set_title('Lab 4: Question 2 v2')

ax.contour(image,levels=[chi2_min+1,chi2_min+2.3,chi2_min+6.17],colors='k',extent=extent)

<matplotlib.contour.QuadContourSet at 0x17b79b640>

Note

Note that the different “slopes” of the contours in the two versions is not because they are different, but because in the imaging sense, due to the differing ranges, the choice of pixel aspect ratio tends to flatten or steepen the apparent slope. The actual chi2 at any given m,b should match between the two.

Question 3¶

Determine the best fit parameters and one-sigma errors from Question 2. The best-fit value can either be the minimum chi2 value or (bonus) by fitting a function to your chi2 values and interpolating the best fit.

Determine the 1-sigma errors on your best-fit parameters. by noting where chi2 = chi2 + 1

msk = chi2 < (np.min(chi2) + 1.)

m_err = (np.max(m_arr[msk]) - np.min(m_arr[msk]))/2.

b_err = (np.max(b_arr[msk]) - np.min(b_arr[msk]))/2.

print('Best fit slope: {:0.2f} +/- {:0.2f} '.format(m_min,m_err))

print('Best fit intercept: {:0.1f} +/- {:0.1f} '.format(b_min,b_err))

Best fit slope: 2.24 +/- 0.10

Best fit intercept: 34.0 +/- 18.0

Cool… our one sigma errors agree with Question 1 from above.

Warning

When looking at the \(\chi^2\) distribution above, it is clear that there is covariance between \(m\) and \(b\) — to get a good fit, higher values of \(b\) force shallower slopes and vice versa. When we are interested in the two dimensional, covariance-included uncertainty (that is, the joint uncertainty), we want the area of this chi2 grid that is parametrized by a \(\Delta \chi^2 +2.3\) from the minimized \(\chi^2\) value. On the other hand, if we care about the individual uncertainties in \(m\) and \(b\), we actually project out of this two dimensional space. In this case, the proper \(\Delta \chi^2\) to use is \(+1\).

Part 2: MCMC Fitting¶

While chi2 is a good method for determining best-fitting values, it less reliable in determining errors on those parameters. If your science question requires good error estimates and/or if your model contains more than a few parameters, Monte Carlo (MCMC) is a popular tool.

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2018ApJS..236…11H/abstract

You will need to install two packages for this work inside of your A330 environment:

conda install emcee

conda install corner

Question 4¶

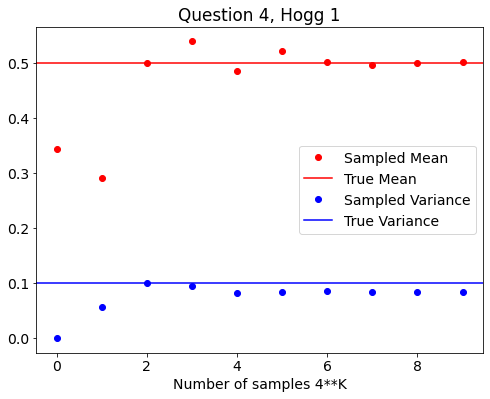

Read Hogg et al. 2018 and do Problems 1-4.

For Problem 1, you are welcome to explore just the mean and varience.

For Problem 2, you have no choice. Use python :)

For Problem 4, I found it easier to do 4b first, then 4a.

Answer for Problem 1 from Hogg et al¶

sample_mean = []

sample_var = []

# INCREASE NUMBER OF SAMPLES IN EACH LOOP

for i in range(10):

K=4**i

# random samples from a uniform distribution between 0-1

x = np.random.rand(K)

mean = (1./K) * np.sum(x) # DEF OF SAMPLE MEAN

var = (1./K) * np.sum((x-mean)**2) # DEF OF SAMPLE VARIANCE

sample_mean.append(mean)

sample_var.append(var)

# PLOT RESULTS ON SAME PLOT

fig,ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,6))

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 14})

ax.plot(np.arange(10),sample_mean,'ro',label='Sampled Mean')

ax.set_title('Question 4, Hogg 1')

plt.axhline(y=0.5,color='r',label='True Mean')

ax.plot(np.arange(10),sample_var,'bo',label='Sampled Variance')

ax.set_xlabel('Number of samples 4**K')

ax.axhline(y=0.1,color='b',label='True Variance')

#ax.set_scale('log')

ax.legend()

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x17db57f40>

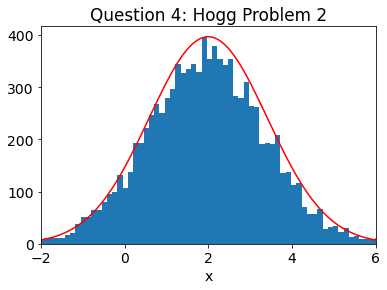

Answer for Problem 2 from Hogg et al 2018¶

def gaussian(x,mu,sig) :

'''

Gaussian distribution

Parameters

----------

x: float array

Values where Gaussian will be evaluated

mu, sig: float

Mean and sigma of the Gaussian

Returns

-------

gaussian

The value of the Gaussian evaluated at x

'''

return np.exp(-0.5*((x-mu)/sig)**2)

mn = 2

sg = np.sqrt(2.)

xk = 0 # INITIALIZE SAMPLER

samples = []

for i in range(10**4):

xp = np.random.normal(xk,1) # PROPOSAL DISTRIBUTION

# GAUSSAIAN SIGMA = 1

r = np.random.rand()

f1 = gaussian(xp, mn, sg) # NEW SAMPLE

f2 = gaussian(xk, mn, sg) # OLD SAMPLE

ratio = f1/f2

if (ratio > r): # ACCEPT OR REJECT?

samples.append(xp)

xk=xp

else:

samples.append(xk)

# PLOT SAMPLES

samples_prob2 = samples # SAVE FOR LATER

n, bins, patches = plt.hist(samples,bins=75)

mx = np.max(n)

# PLOT TRUTH

a=np.arange(1000)/100. - 3.

true_dist = gaussian(a, mn, sg)

plt.plot(a,mx*true_dist,'r')

plt.xlim(-2,6)

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.title('Question 4: Hogg Problem 2')

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Question 4: Hogg Problem 2')

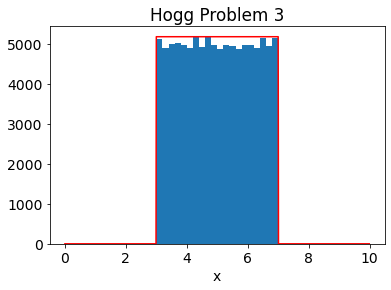

Answer for Problem 3 from Hogg et al 2018¶

def pdf3(x):

'''

Top Hat between 3 to 7 distribution for Problem 3

Parameters

----------

x: float array

Values where Top Hat will be evaluated

Returns

-------

p

returns 1 if inside tophat, 0 if outside

'''

if (x >= 3) & (x<=7):

p = 1.

else:

p=0.

return p

xk = 6. # NEED TO START INSIDE DISTRIBUTION\

samples = []

for i in range(10**5):

xp = np.random.normal(xk,1) # PROPOSAL DISTRIBUTION

r = np.random.rand()

f1 = pdf3(xp) # SAMPLE NEW

f2 = pdf3(xk) # SAMPLE NEW

ratio = f1/f2

if (ratio > r): # COMPARE

samples.append(xp)

xk=xp

else:

samples.append(xk)

# PLOT SAMPLES

n, bins, patches = plt.hist(samples,bins=20)

mx = np.max(n)

# PLOT TRUTH

a=np.arange(1000)/100.

true_dist= (a >=3) & (a<=7)

plt.plot(a,mx*true_dist,'r')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.title('Hogg Problem 3')

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Hogg Problem 3')

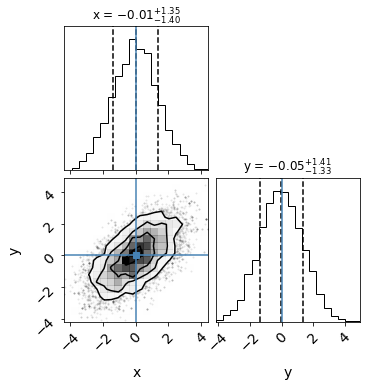

Answer for Problem 4a from Hogg et al 2018¶

from scipy import stats

def pdf4a(x,y) :

'''

Two dimensional Gaussian distribution,

Parameters

----------

x,y: float array

Values where 2D Gaussian will be evaluated

mu, sig: float

Mean and sigma of the Gaussian

Returns

-------

gaussian

The value of the Gaussian evaluated at x, y

'''

mean = [0,0]

cov = [[2.0,1.2],[1.2,2.0]]

gauss = stats.multivariate_normal(mean, cov)

return gauss.pdf([x,y])

xk = 6. # NEED TO START INSIDE DISTRIBUTION

yk = 5.

xsamples, ysamples = [], []

for i in range(10**4):

ind = [[1.0,0],[0,1]]

xp,yp = np.random.multivariate_normal([xk,yk],ind)

r = np.random.rand()

f1 = pdf4a(xp,yp)

f2 = pdf4a(xk,yk)

ratio = f1/f2

if (ratio > r):

xsamples.append(xp)

xk=xp

ysamples.append(yp)

yk=yp

else:

xsamples.append(xk)

ysamples.append(yk)

data = np.column_stack((ysamples,xsamples))

import corner

figure = corner.corner(data, truths=[0,0],labels=["x", "y"],

quantiles=[0.16, 0.5, 0.84],show_titles=True,

title_kwargs={"fontsize": 12})

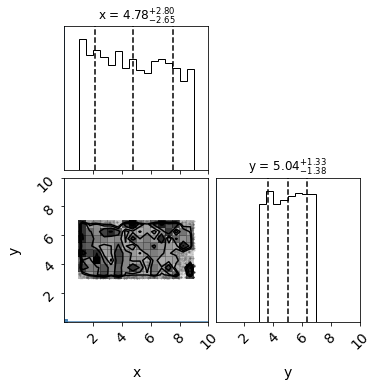

Answer for Problem 4b from Hogg et al 2018¶

def pdf4b(x,y):

'''

2D Top Hat distribution for Problem 4

Hard-wired between 3-7

Parameters

----------

x,y: float array

Values where Top Hat will be evaluated

Returns

-------

p

returns 1 if inside tophat, 0 if outside

'''

if (x >= 3) & (x<=7) & (y >= 1) & (y <=9):

p = 1.

else:

p=0.

return p

xk = 6. # NEED TO START INSIDE DISTRIBUTION

yk = 5.

xsamples, ysamples = [], []

ind = [[2.0,1.2],[1.2,2.0]]

for i in range(10**4):

xp,yp = np.random.multivariate_normal([xk,yk],ind)

r = np.random.rand()

f1 = pdf4b(xp,yp)

f2 = pdf4b(xk,yk)

ratio = f1/f2

if (ratio > r):

xsamples.append(xp)

xk=xp

ysamples.append(yp)

yk=yp

else:

xsamples.append(xk)

ysamples.append(yk)

data = np.column_stack((ysamples,xsamples))

figure = corner.corner(data, truths=[0,0],labels=["x", "y"],

quantiles=[0.16, 0.5, 0.84],show_titles=True,

title_kwargs={"fontsize": 12},range=([0,10],[0,10]))

Question 5¶

While the above problems should give you a sense for how MCMC works, most reseach problems use standard packages to run MCMC. MCMC packages in astronomy include emcee, MultiNest, Dynasty.

Write an MCMC to evaluate the data in Question 1+2 above using emcee. We suggest checking out the guide to MCMC here:

https://prappleizer.github.io/Tutorials/MCMC/MCMC_Tutorial.html

We suggest 20 walkers and 2000 steps for your sampler. Plot both the sampler chains and a corner plot of the results.

Compare the best fit values for m and b from the chi2 and MCMC, as well as their errors.

import emcee

import corner

# LOAD DATA FROM HOGG et al 2010, Table 1

data = ascii.read('hogg_2010_data.txt')

# SKIP THE FIRST FEW DATA POINTS

m=data['ID'] > 4

data=data[m]

def lnprob(theta,x,y,sigma):

'''

Evaluate whether to accept or

Parameters

----------

x,y: float array

Values where Top Hat will be evaluated

Returns

-------

p

returns 1 if inside tophat, 0 if outside

'''

lp = lnprior(theta)

if not np.isfinite(lp):

return -np.inf

return lp + lnlike(theta, x, y, sigma)

def lnprior(theta):

'''

Evaluate whether sample falls inside of priors

Parameters

----------

theta: float array

Current values of fitted parameters

Returns

-------

returns 0 if inside prior, -inf if outside

'''

if (0 < theta[0] < 5) & (-30 < theta[1] < 200):

return 0.0

return -np.inf

def lnlike(theta,x,y,sigma):

'''

Evaluate the log-likelihood

Parameters

----------

theta: float array

Current values of fitted parameters

x,y, sigma: float arrays

Data points and one sigma errors

Returns

-------

lnl

log-likelihood value

'''

# MAKE MODEL

model = theta[0]*x + theta[1]

# EVALUATE LIKELIHOOD

chi2 = ((y - model)**2)/(sigma**2)

lnl = -0.5 * np.sum(chi2)

return lnl

def initialize_walkers(mguess,bguess):

'''

Initialize the walkers using an initial guess

Parameters

----------

mguess, bguess: float value

Rough initial guess of parameters

Returns

-------

ndim, nwalkers, p0

'''

# Two free parameters (m,b) and 20 walkers

ndim, nwalkers = 2, 20

p0 = np.random.rand(ndim * nwalkers).reshape((nwalkers, ndim))

# initialize slope

p0[:,0] = (p0[:,0]*4. - 2) + mguess

# initialize intercept

p0[:,1] = (p0[:,1] * 60 - 30) + bguess

return ndim,nwalkers,p0

mguess = 2

bguess = 30

max_n=3000

ndim, nwalkers, p0 = initialize_walkers(mguess,bguess)

# INITIALIZE SAMPLER

sampler = emcee.EnsembleSampler(nwalkers, ndim, lnprob, args=(data['x'],data['y'],data['sigma_y']))

# RUN MCMC

pos, prob, state = sampler.run_mcmc(p0, max_n)

# As a bonus, we can determine the number of burnin samples and whether the chains converged.

tau = sampler.get_autocorr_time(tol=0)

burnin = int(2 * np.max(tau))

converged = np.all(tau * 100 < sampler.iteration)

print('Number of initial burnin samples:',burnin)

print('Did the chains converge?',converged)

Number of initial burnin samples: 54

Did the chains converge? True

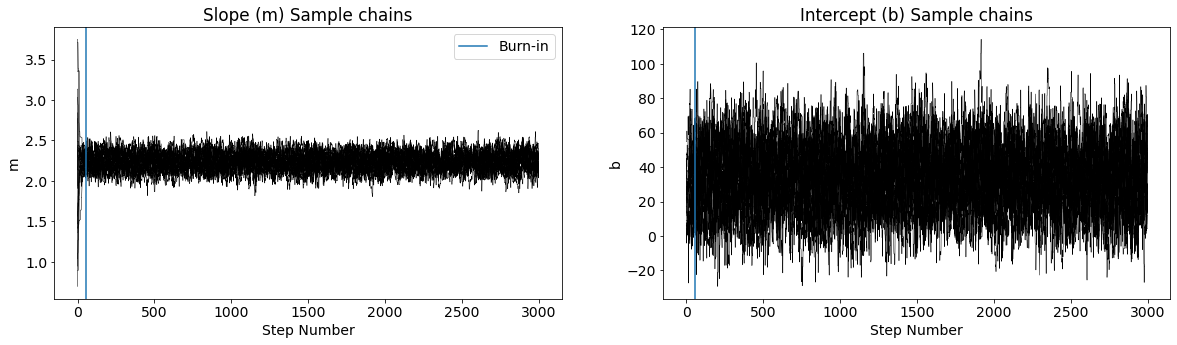

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2,figsize=(20,5))

for ii in range(20):

ax1.plot(sampler.chain[ii,:,0], color="k",linewidth=0.5)

for ii in range(20):

ax2.plot(sampler.chain[ii,:,1], color="k",linewidth=0.5)

ax1.set_ylabel('m')

ax2.set_ylabel('b')

ax1.set_xlabel('Step Number')

ax2.set_xlabel('Step Number')

ax1.set_title('Slope (m) Sample chains')

ax2.set_title('Intercept (b) Sample chains')

ax1.axvline(burnin,label='Burn-in')

ax2.axvline(burnin)

ax1.legend()

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x1819a58e0>

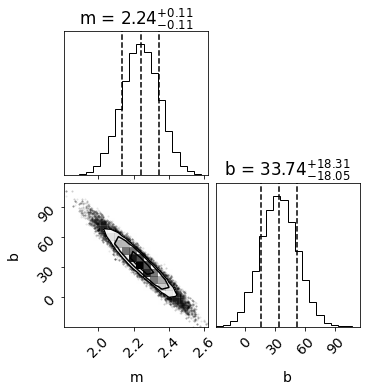

# PLOT CORNER

labels=['m','b']

burnin = 100

samples = sampler.chain[:, burnin:, :].reshape((-1, ndim))

fig = corner.corner(samples, labels=labels,show_titles=True,quantiles=[0.16, 0.5, 0.84])

The MCMC returns similar best fit values and one-sigma errors as our chi2 method above!